Salsa dancing in Taiwan. Sexism in the SS. Dowry deaths in India. Child activists in the abortion wars. Mayan women writing plays critical of the patriarchy. Female architects and textile makers. Female coal miners. Female slave owners before and during the Civil War.

Salsa dancing in Taiwan. Sexism in the SS. Dowry deaths in India. Child activists in the abortion wars. Mayan women writing plays critical of the patriarchy. Female architects and textile makers. Female coal miners. Female slave owners before and during the Civil War.

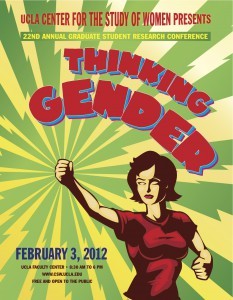

All these subjects, and more, were part of the 22nd annual “Thinking Gender” conference, held at UCLA. Organized by the university’s Center for the Study of Women, the conference hosted more than 120 scholars (mostly female) from around the world. There were four sessions, each with five panels apiece. In short: A whole lot of gender relations talks to cover. Here are some of the highlights:

Gender Stereotypes

“Dirty Work: Women and Unexpected Labor.” The labor in question referred to everything from prison guards to coal miners, and this panel was well worth attending because it was both interesting and discomfiting. The first scholar to present in this panel was Shelly M. Cline, a history student from the University of Kansas. Her paper was on gender discrimination in the SS, particularly against women who guarded prisoners in the Auschwitz death camp. “The state asked them to do a man’s job, but didn’t offer them an equal partnership,” Cline said, going on to talk about how, as a result of being treated badly by their male colleagues, many of these women took out their frustrations on prisoners in increasingly terrible ways as a way to try to get respect from the men. (That is not to say, Cline added, that these women’s actions were any more brutal overall than their male colleagues’.) When WWII was over, and the Allies put these women on trial, they only won equality by being given punishments as severe as the men.

Cline’s work put an unsettlingly human face on these women who most would see as monsters. Of course, sexism in the workplace is never okay. But is oppression ever an excuse to oppress others weaker than you? And on a side topic, is brutality committed by women worse than that committed by men, since we are expected to be the gentler sex?

The questions raised by Cline’s work were also addressed in a paper by University of Houston history scholar Katie Smart. Smart explored the lives of women who owned slaves before and during the Civil War. Lots has been written about female slaveowners, and much of it paints these women as more compassionate than the males, Smart said. But when she did her own research, which included reading accounts from former slaves, Smart found this portrayal was a lie. “There was more hatred and violence than normal,” Smart said, adding that many women running plantations treated their slaves, particularly the women slaves, like cattle for breeding. Unlike enslaved men, enslaved women were also less likely to run away permanently, since they were unwilling to leave children and other family members behind on the plantation. And when they returned, they received severe punishment from their mistresses.

Reproductive Rights

The importance of female complicity in our own oppression was also touched on in a later session on reproductive rights. Jennifer L. Holland, a history scholar at University of Wisconsin, Madison presented a fascinating paper on the recruitment of children and teens by the anti-choice movement. According to Holland, one of the first anti-choice protests, held in 1967, encouraged women in the movement to bring their children to the march as tangible reminders of “abortion survivors.” Since then, anti-choice women, and their children, have become the face of the movement. One tactic for recruiting kids involved fetus dolls, which became a favored toy for little girls in the movement. For older kids, anti-choice teachers, school nurses and cafeteria ladies were known to carry around fetus models to show to high school girls who might consider abortion, Holland said. When pro-choice activists started fighting back against these tactics, the growing evangelical home schooling movement (where mothers are overwhelmingly the teachers) took children out of the possibly corrupting public school system altogether. As a result, Holland said, children are being trained as activists much younger.

Liberation In Unlikely Places.

The conference’s plenary session touched on lighter matters. I-Wen Chang, a dance scholar from UCLA, talked about salsa dancing, which is now incredibly popular in Taiwan. “Salsa breaks all the rules,” Chang said. How? Well, for these women, salsa steps are subversive, because they go against traditional Chinese ideas about how female bodies should move, Chang said. Apparently, swaying your hips is considered improper. Also, the male role in the dance is more egalitarian, so the dance is less about leading and more about partnering. But unfortunately, salsa is not quite the feminist boon to the Republic of China as one might hope. Chang added that men often partner each other, and this is seen as empowering and a way to bond socially, but that women aren’t allowed to do the same. Also, salsa clubs have become networking stations for the social elite. So, if a woman shows up at such a club without a male partner, that is a bad thing. But the men can happily show up stag and dance with each other.

Yvette Martinez-Vu, a theater scholar also from UCLA, spoke at the plenary about Mayan women in Chiapas, Mexico, and their attempts to educate and empower their fellow women through theater. A group called Fortaleza de la Mujer Maya does plays about domestic relationships in the Maya community, and those plays often highlight the sexist culture that keeps wives from making major family decisions, Martinez-Vu said, and encourages women to challenge their roles. They also offer practical solutions, such as computer and business classes, Martinez-Vu said.

The Evils of Gender Oppression

The challenges of female empowerment in a patriarchal society was a major theme at the conference. In the final session, I attended a panel where two scholars dealt with domestic violence against women in India. Roy Juhi, a global gender studies scholar at the State Unversity of New York, Buffalo, is a from Bihar, India. For her, the damage caused by India’s dowry system is personal as well as political. “I grew up with this,” she said. “A lot of my friends got married.” The dowry tradition, though officially illegal, requires the bride’s family to pay the groom’s family a certain amount (negotiated according to wealth and resources) upon marriage. Eighty percent of Indian marriages involve dowries, and far too often, the groom’s family feels cheated by this negotiation, and take out their anger on the bride, Juhi said. In the worst case scenario, they kill the bride and then claim it’s suicide. Juhi said there are as many as 2,400 dowry deaths a year, and most remain unprosecuted, because the laws protecting brides are full of loopholes favoring the perpetrators.

Even when this situation doesn’t end in murder, domestic violence is common. “Fifty-nine percent of married women in Bihar are exposed to domestic violence,” Juhi said, adding that it doesn’t help that Hindu tradition requires that women stay with their husbands no matter what. A subsequent paper, by Julia Kowalski of the University of Chicago, talked about that violence, but revealed a twist: while we often assume the abuser must be the husband, that is not always the case. Kowalski spoke of a case study where one young bride was being abused by her sister-in-law, who hit her under the pretext of training her to be a proper wife. The authorities working on the case decided that mediation was the way to resolve the problem, Kowalski said, a decision frowned upon by most domestic abuse experts who think this gives too much power to the abuser. However in this case, it helped, Kowalski said, adding that the complexities of interpersonal relationships should be taken into account when dealing wth problems such as domestic abuse.